Biography

Kara Walker (1960-):

Kara Walker is an African-American artist who rose to fame for her use of large paper silhouettes to explore social issues surrounding gender, race and black history.

Synopsis

Kara Walker was born in 1969 in Stockton, California. At the Rhode Island School of Design, Walker began working in the silhouette form. In 1994, her work appeared in a new-talent show at the Drawing Center in New York and she became an instant hit. In 1997, she received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation "genius grant." Since then, Walker's work has been exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide.

Early Life

Kara Walker was born in Stockton, California, on November 26, 1969. Raised by a father who worked as a painter, Walker knew by age 3 that she wanted to become an artist as well. Initially dreaming of creating fine art, Walker's ambitions changed as she grew older; she began experimenting with various avant-garde styles, creating pieces in order to tell a story or make a statement rather than achieve beauty or perfection. "I guess there was a little bit of a slight rebellion, maybe a little bit of a renegade desire that made me realize at some point in my adolescence that I really liked pictures that told stories of things—genre paintings, historical paintings—the sort of derivatives we get in contemporary society," Walker stated in 1999, during an interview with New York's Museum of Modern Art. At a young age, Walker moved with her family to Atlanta, Georgia, where she would spend the rest of her childhood and later attend the Atlanta College of Art. She earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting and printmaking from the school in 1991. Three years later, in 1994, she received a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting and printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design, located in Providence.

Career Success

The same year that she graduated from RISD, Walker debuted a mural at the Drawing Center in New York City, entitled "Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart." It wasn't just the theme of the piece that caught the attention of critics, but its form: black-paper silhouette figures against a white wall.

The mural launched Walker's career, also making her one of the leading artistic voices on the subject of race and racism. Over the course of her impressive career, Walker has had solo exhibitions at a range of institutions, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Tate Liverpool in Liverpool, Merseyside, England; the Metropolitan Museum of Art of in New York; and the Walker Art Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In 2007, TIME magazine named Walker to it's prestigious "TIME 100" list. According to one TIME magazine article: "[Walker] raucously engages both the broad sweep of the big picture and the eloquence of the telling detail. She plays with stereotypes, turning them upside down, spread-eagle and inside out. She revels in cruelty and laughter. Platitudes sicken her. She is brave. Her silhouettes throw themselves against the wall and don't blink."

In addition to being well-received, however, Walker's work has stirred controversy among some. In 1997, a group of older African-American artists criticized Walker for using what they considered to be black stereotypes in her art, and even tried to organize a boycott of her work.

In December 2012, the Newark Library in New Jersey covered up a large Walker drawing, part of which depicted a white man holding the head of a naked black women to his groin, after employees and patrons complained about the work. Library officials later uncovered the drawing, allowing it to be shown.

A longtime resident of New York City, Walker was a professor of visual arts in the MFA program at Columbia University. In 2015, Walker began a five-year term as Tepper Chair in Visual Arts at Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of the Arts.

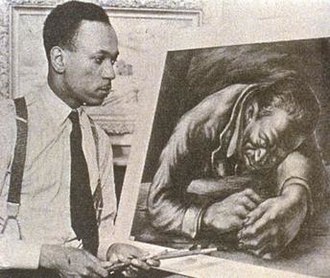

Charles White (1918 – 1979):

Charles Wilbert White, Jr. was an American artist known for his chronicling of African American related subjects in paintings and murals. White's best known work is The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, a mural at Hampton University. In 2018, the centenary year of his birth, the first major retrospective exhibition of his work was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art.

Early life and education

Charles Wilbert White was born on April 2, 1918, to Ethelene Gary, a domestic worker, and Charles White Sr, a railroad and construction worker, on the South Side of Chicago. His parents never married and his mother raised him -- as she had no child care, she would often leave him at the public library. There White developed an affinity for art and reading at a young age. White's mother bought him a set of oil paints when he was seven years old, which hooked White on painting. White also played music as a child, studied modern dance, and was part of theatre groups; however, he stated that art was his true passion. White's mother also took him to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he would read and look at paintings—developing a particular interest in the works of Winslow Homer and George Inness. During the Great Depression, White tried to conceal his art passion in fear of embarrassment; however, this ended when White got a job painting signs at the age of fourteen. Since White had little money growing up, he often painted on whatever surfaces he could find including shirts, cardboard, and window blinds. White learned how to mix paints by sitting in everyday for a week on an Art Institute sponsored painting class that was taking place at a park near his home. His mother re-married when White's father died in 1926. She married a steel mill worker who would become an abusive alcoholic, especially towards a young White, leaving him to escape into art. This is also the same year his mother began sending him to Mississippi twice a year to his aunts, Hasty Baines and Harriet Baines, where he would learn about his heritage and African American Southern folklore - these themes would heavily influence his art for the rest of his career as an artist. An early activist, as a teenager, he volunteered his talents and became the house artist at the National Negro Congress in Chicago. White won a grant during the seventh grade to attend Saturday art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. After reading Alain Locke's book The New Negro: An Interpretation, a critique of the Harlem Renaissance, White's social views changed. He learned after reading Locke's text about important African American figures in American history, and questioned his teachers on why they were not taught to students in school, causing some to label him a "rebel problematic child". White did not graduate from high school, having flunked a year due to his refusal to attend class after being disillusioned with the teaching system. He was encouraged by his art teachers to submit his art works and won various scholarships that would later be taken away from him as an "error" and given to a whites instead. He was admitted to two art schools, each then pulled his acceptance because of his race. White ultimately received a full scholarship to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. While in school, White identified Mitchell Siporin, Francis Chapin, and Aaron Bohrod as his influences. He was an excellent draftsman, completing five drawing courses and received a final "A grade". To pay the costs of materials in art school, White became a cook, using his mother's instruction and recipes. White later became an art teacher at St. Elizabeth Catholic High School to pay the costs for art material. White was hired Works Progress Administration artist, and was later jailed for forming a union with fellow black artists who were being treated unfairly and wanted equal rights.

Career

In 1938, White was hired by the Illinois Art Project a state affiliate of the Works Progress Administration. His work received an extended showing at the Chicago Coliseum during the Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro which was part of an exposition commemorating the 75th anniversary of Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery. An important figure in what became known as the Chicago Black Renaissance, White taught art classes at the Southside Community Art Center. Following his first show at Paragon Studios in Cincinnati in 1938, White's work was exhibited widely throughout the United States, including, among many others, exhibitions at the Roko Gallery, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. White also showed at the Palace of Culture in Warsaw and the Pushkin Museum. In 1976 his work was featured in Two Centuries of Black American Art, LACMA's first exhibition devoted exclusively to African-American Artists. White moved to New Orleans in 1941 to teach at Dillard University. Beginning in that year, he was married briefly to famed sculptor and printmaker, Elizabeth Catlett who also taught at Dillard. He served in the US Army during WWII, but was discharged when he contracted tuberculosis. White and Catlett moved to New York City and also studied together at an arts collective in Mexico City. In 1958, due to problems White experienced with his breathing, he was persuaded to move to Los Angeles for its drier more mild climate. From 1965 to his death in 1979, White taught at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. On faculty at Otis, he was a beacon for African American artists who came to study with him. Among those he taught were Alonzo Davis, David Hammons, and Kerry James Marshall. An elementary school was named after him and is located on the former Otis College campus. White's best known work is mural The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy at Hampton University. Measuring around 12 feet by seven feet, the mural depicts a number of notable African-Americans including Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Peter Salem, George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Marian Anderson. White was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1972. White's works are in the collections of a number of institutions, including Atlanta University, the Barnett Aden Gallery, the Deutsche Academie der Kunste, the Dresden Museum of Art, Howard University, the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Oakland Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Syracuse University and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The CEJJES Institute of Pomona, New York, owns a number of White's works and has established a dedicated Charles W. White Gallery.

Reception

In 1982 a retrospective exhibition of White's work was held at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In the 1990s, the idea of staging a major traveling retrospective exhibition arose. Ultimately, over approximately a ten year period, staff from the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art attempted to locate various White pieces to put together an extensive exhibition of his work. The exhibition opened in Chicago in 2018, traveling to New York City and Los Angeles. White "was a humanist, drawn to the physical body and more literal representations of the lives of African-Americans", according to Lauren Warnecke for the Chicago Tribune. Washington Post art critic, Philip Kennicott finds White's work central to American art. "Grace, passion, coolness, toughness, [and] beauty" mark White's work, according to Holland Cotter in the New York Times; White had "the hand of an angel" and "the eye of a sage".

Barkley Leonard Hendricks (1945 – 2017):

Barkley L. Hendricks as a contemporary American painter who made pioneering contributions to black portraiture and conceptualism. While he worked in a variety of media and genres throughout his career (from photography to landscape painting), Hendricks' best known work took the form of life-sized painted oil portraits of Black Americans.

Early life

Born on April 16, 1945, in the North Philadelphia neighborhood of Tioga. Barkley Leonnard Hendricks was the eldest surviving child of Ruby Powell Hendricks and Barkley Herbert Hendricks. His parents had moved to Philadelphia from Halifax County, Virginia during the Great Migration when large numbers of African Americans moved out of the rural Southern United States. Hendricks attended Simon Gratz High School and graduated in 1963. He attended Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). After graduating PAFA in 1967, Hendricks decided to enlist in the New Jersey National Guard and found work as an arts and crafts teacher with the Philadelphia Department of Recreation. In 1970, he began attending Yale University and graduated in 1972 with both a bachelor's and master's degree.

Career

Hendricks was Professor Emeritus of Studio Art at Connecticut College, where he taught drawing, illustration, oil and watercolor painting, and photography, from 1972 until his retirement in 2010. In the mid-1960s while touring Europe, he fell in love with the portrait style of artists like van Dyck and Velázquez. As the Black Power movement gained momentum, Hendricks set about the change what he saw in Europe by correcting the balance, in life-size portraits of friends, relatives and strangers encountered on the street that communicated a new assertiveness and pride among black Americans. In these portraits, he attempted to imbue a proud, dignified presence upon his subjects. He frequently painted black Americans against monochrome interpretations of urban northeastern American backdrops. Hendricks' work is considered unique in its marriage of American realism and post-modernism. Although Hendricks did not pose his subjects as celebrities, victims, or protesters, the subjects depicted in his works were often the voices of the under-represented blacks of the 1960s and 1970s. Hendricks even stood alongside his subjects and featured himself in works, like in Brilliantly Endowed (Self portrait), 1977 where he painted himself nude in response to an art critic's comments on his show. In 1969, he painted one of his first portraits, Lawdy Mama, which depicts a young woman (his second cousin) in the style of a Byzantine icon with gold leaf surrounding her modernly dressed figure and Angela Davis style afro on an arched canvas. Hendricks said the portraits were about people he knew, and were only political because of the culture of the time. Hendricks' work is included in a number of major museum collections, including the National Gallery of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the National Endowment for the Arts.[7]1 In the 1970s, he produced a series of portraits of young black men, usually placed against monochromatic backdrops, that captured their self-assurance and confident sense of style.[3] In 1974, Hendricks painted What’s Going On, one of his best-known portraits, named after Marvin Gaye's single What's Going On.[8] In 1977, Hendricks was shown most conspicuously in a full-frontal self-portrait in which he is wearing only sports socks and sneakers, some jewelry, glasses and a white leather applejack hat. He stopped painting from 1984 to 2002 to concentrate on photography of mainly on jazz musicians.In 1995 while traveling with Whitney Museum of American Art, he was the primary revelation in Black Male. Hendricks' first career painting retrospective, titled Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool, with works dating from 1964 to 2008, was organized by Trevor Schoonmaker at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in spring 2008, traveled to the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Santa Monica Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Hendricks's work was featured on the cover of the April 2009 issue of Artforum Magazine, with an extensive review of Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool. Hendricks was represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City.

Personal life and death

Hendricks married Susan Hendricks in 1983. They were married until his death in 2017. While touring Europe in the mid-1960s in his visits to the museums and churches of Britain, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands, he found his own race was absent from Western art, leaving a void that troubled him. Hendricks died in his home on the morning of April 18, 2017, in New London, Connecticut from a cerebral hemorrhage.

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937):

Henry Ossawa Tanner was an American painter who frequently depicted biblical scenes and is best known for the paintings "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus," "The Banjo Lesson" and "The Thankful Poor." He was the first African-American painter to gain international fame.

Synopsis

Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on June 21, 1859. As a young man, he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1891, Tanner moved to Paris, and after several exhibits, gained international acclaim—becoming the first African-American painter to receive such attention. "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus" is one of his most famous works. He's also known for the paintings "The Banjo Lesson" and "The Thankful Poor." Tanner died in 1937 in Paris, France.

Early Life

A pioneering African-America artist, Henry Ossawa Tanner was born on June 21, 1859, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The oldest of nine children, Tanner was the son of an Episcopal minister and a schoolteacher.

When he was just a few years old, Tanner moved with his family to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he would spend most of his childhood. Tanner was the beneficiary of two education-minded parents; his father, Benjamin Tanner, had earned a college degree and become a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopalian Church. In Philadelphia, Tanner attended the Robert Vaux School, an all-black institution and of only a few African-American schools to offer a liberal arts curriculum.

Despite his father's initial objections, Tanner fell in love with the arts. He was 13 when he decided he wanted to become a painter, and throughout his teens, he painted and drew as much as he could. His attention to the creative side was furthered by his poor health: After falling significantly ill as a result of a taxing apprenticeship at a flourmill, the weak Tanner recuperated by staying home and painting.

Finally, in 1880, a healthy Tanner resumed a regular life and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. There, he studied under Thomas Eakins, an influential teacher who had a profound impact on Tanner's life and work.

Tanner ended up leaving the school early, however, and moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he would teach art and run his own gallery for the next two years.

In 1891, Tanner's life took a dramatic turn with a visit to Europe. In Paris, France, in particular, Tanner discovered a culture that seemed to be light years ahead of America in race relations. Free from the prejudicial confines that defined his life in his native country, Tanner made Paris his home, living out the rest of his life there.

Artistic Success

Tanner's greatest early work depicted tender African-American scenes. Undoubtedly his most famous painting, "The Banjo Lesson," which features an older gentleman teaching a young boy how to play the banjo, was created while visiting his family in Philadelphia in 1893. The following year, he produced another masterpiece: "The Thankful Poor."

By the mid-1890s, Tanner was a success, critically admired both in the United States and Europe. In 1899, he created one of his most famous works, "Nicodemus Visiting Jesus," an oil painting on canvas depicting the biblical figure Nicodemus's meeting with Jesus Christ. For the work, he won the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts' Lippincott Prize in 1900.

Also in 1899, Tanner married a white American singer, Jessie Olssen. The couple's only child, Jesse, was born in 1903.

Throughout much of the rest of his life, even as he shifted his focus to religious scenes, Tanner continued to receive praise and honors for his work, including being named honorary chevalier of the Order of the Legion Honor—France's most distinguished award—in 1923. Four years later, Tanner was made a full academician of the National Academy of Design—becoming the first African-American to ever receive the distinction.

Death and Legacy

Henry Ossawa Tanner died at his Paris home on May 25, 1937. In the ensuing years, his name recognition dipped. However, in the late 1960s, beginning with a solo exhibition of his work at the Smithsonian, Tanner's stature began to rise. In 1991, the Philadelphia Museum of Art assembled a touring retrospective his paintings, setting off a new wave of interest in his life and work.

Betye Saar (1926-):

Betye Saar is best known for her art work that critiques American racism toward blacks.

Synopsis

Betye Saar was born July 30, 1926 in Los Angeles, California. Saar's artwork addressed American racism and stereotypes head on, typically of the assemblage format. One of her more famous works, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, confronted the myths and prejudice of the syrup bottle.